Tameshigiri Cutting Test On Japanese Swords

TAMESHI-GIRI – CUTTING TESTS ON JAPANESE SWORDS

The effectiveness or efficiency of their weapon is obviously of paramount importance to any soldier or warrior, whose life might depend on it. This is quite understandable and it was necessary for the owner of the weapon to have complete confidence in it.So it was for the samurai, but for most of their history, certainly up to the latter part of the 16th century, constant warfare was enough to test most forms of weaponry. This included bladed varieties such as yari (spears) naginata (halberds) and swords. It was no problem to discard a broken or blunted instrument as new ones were constantly coming from the forges of swordsmiths, principally from the provinces of Bizen (present day Okayama prefecture) and Mino (present day Gifu prefecture). However, with the dawn of the great peace heralded by the victory of Tokugawa Ieyasu, at the definitive battle of Sekigahra in 1600, and the establishing of the Tokugawa shogunate, the everyday opportunity to use a sword was greatly reduced.

The execution ground with three heads displayed

Since the cessation of the sengoku jidai or the country at war, fundamental changes in swordmaking had occurred. Mostly, swords had previously been purely practical things and often shortcuts had been made in the production process and economies made in the materials used. Of course, there are swords of great antiquity which are unsurpassed in excellence but the vast majority were not of this standard, especially in the Muromachi period (1450-1580).Without the pressures of producing large quantities of blades to arm the hundreds of thousands under arms, swordsmiths could concentrate on making better and more artistic blades. Influenced by the prevailing Momoyama culture in Kyoto the Imperial capital, swordsmiths at the end of the 16th century began to make more decorative or artistically pleasing swords. The more picturesque hamon or hardened edge, as well as more ornate horimono or carvings with fewer religious subjects, were obvious manifestations of this. Now that raw materials were increasingly distributed from central sources, the metal or jigane, ceased to show the individual regional characteristics of earlier times and now demonstrated a uniformity not seen before. However, in the early 1600’s, whilst the living memory of real combat still existed, swords were shaped like shortened versions of the oversize blades of the 14th century, a time which might be referred to as a “golden age” of sword manufacture.

Woodblock print of an execution

As the Tokugawa shogunate became established in their capital, a small town in the east of the country named Edo (present day Tokyo) many swordsmiths flocked to this expanding location to take advantage of the prevailing martial atmosphere. At the same time, the Imperial capital of Kyoto attracted a good number swordsmiths whose families originated in the sword-making culture of Mino province. Meanwhile, close to Kyoto, the city of Osaka was becoming a thriving centre of commerce and here swordsmiths established themselves to supply the affluent merchant classes as well as the resident samurai. In addition to these three cities, some fortunate swordsmiths were directly retained by some of the great daimyo or feudal lords, positions both they and their ancestors often held for many generations.

The shogunate enforced the peace with an authority based on military strength and it would be no exaggeration to call this a “police state”. Many rules and regulations affected all aspects of life, and social classes were fixed absolutely with social mobility almost unheard of. At the top of this structure were the warrior class, the samurai, who formed about 10% of the total population. It was said to be rule by the samurai for the samurai. The wearing of the daisho or pair of swords was compulsory and defined the status of the samurai as a warrior.

As the peace progressed almost uninterrupted into the first half of the 17th century, the amount of samurai with actual battle experience was fewer and fewer but the samurai were expected to be constantly at a high level of readiness. Their very existence as a class supposedly depended on their ability in the martial arts, predominantly skill with swords. To some, this posed the problem of whether or not their sword was able to really be relied on in combat, in other words would it not bend or break and would it cut efficiently? At the same time a host of laws were enacted by the shogunate government, restricting the length of swords. In many cases it seems that this meant that existing swords needed to be shortened and this also worried some that their weapon was no longer effective.

To the concerned samurai, the testing of his sword was the obvious response and this seems to have been recognised by the government who appointed official testers. The execution grounds, especially in Edo, provided excellent facilities and also “raw materials” for tests that could be considered as useful. Especially in and around the Kanbun (1661-72) and Enpo (1673-80) periods, many swords were officially tested at these places. This may have been due to a raft of new sword legislation at that time that resulted in many sword alterations. It was also a reflection of the development of shinai- kendo. The shinai was a bamboo sword that was straight and swords made at that time, especially in Edo had very shallow curvature in an attempt to replicate the shinai. This is still known as the Kanbun-shinto sugata or “the new-sword shape of the Kanbun period”.

To a few who wished to test their swords, the illegal form of testing known as tsuji-giri or street-cutting was resorted to. In this instance the owner would lurk in some dark street corner with his sword and cut down the first innocent passer-by. Ironically, the most well authenticated case of tsuji-giri was performed on a famous Edo swordsmith named Hankei, some of whose swords themselves were inscribed with the results of cutting tests. Although a grim situation, such instances appear to have been so common that a number of amusing stories are told. For instance, a jujitsu instructor was walking in town when he saw a samurai on a street corner, suddenly draw his sword to cut him down. He acrobatically executed three somersaults and from a safe distance, put out his tongue at the samurai and went on his way.

In another, a lowly beggar sleeping on the roadside had been struck several times during the night, by samurai with worthless blunt swords in an attempt to test their swords on the beggar. On waking he grumbled: “There is no peaceful rest even for a worm such as myself, bad men have beaten me (not cut me!) during my sleep”. These tales also illustrate the arrogant contempt in which the samurai held the lower classes.

The main and official testers in Edo were the Yamada family who had the shogun’s patronage. A series of progressively difficult cuts were devised by them that were to be performed on a corpse, although there are recorded tests being made on live bodies! In fact, the black humour of this situation may be seen in an incident quoted in the appendix of Huncho Gunkiko. In an estate in Dewa Province a robber, who performed as a puppet showman during the day and a robber at night, although a powerfully built man was caught and condemned to death. The tester, named Shoami Dennosuke, was instructed to cut the robber in kesa-giri (from shoulder to hip). The robber was prepared in the stocks and apparently the following dialogue took place:

Robber: “Is it you that will cut me down?”

Shoami: “ Yes, you must be cut alive as you are sentenced”.

Robber: “In what way will you cut me?”

Shoami: “I shall cut you in the kesa style”

Robber: It is too cruel to be cut through alive”

Shoami: “It is the same before or after dearth”.

Robber: “If I had known it before, I would have swallowed a couple of big stones to spoil your sword”.

After execution, by beheading or occasionally by crucifixion, a body was released to the tester who was a skilled swordsman. It was decided in conjunction with the sword’s owner, which cut was to be used, and the body was arranged accordingly. If the sword to be tested was owned by the shogun then many official witnesses attended the test and strict formalities were observed but this does not seem to always be the case. The handling of the corpse was by members of the Eta or hinin, the outcasts or untouchable class, as in Buddhist lore, such work was considered “unclean”.

It seems that the most popular cut was that known as dō. This was a cut through the waist area and for a dō cut the body was arranged on an earth mound called the dodan. The limbs of the corpse were tied onto wooden stakes whilst the torso rested on the mound and the cuts were made. Often more than one body might be piled on top of each other and multiple dō could be cut in a single cutting action.

A body arranged on the dodan in preparation for a do cut

Another cut was the previously mentioned kesa-kiri which is still a favoured cut in modern tameshigiri as well as in Iai-do. In this cut, the blade enters in the shoulder at the base of the neck and exits the body at the hip, following the line of the collar of a Japanese robe, the Kesa. This is particularly difficult as there is considerable amount of body to cut through. For kesa-kiri a different position must be adopted and the corpse or target needs to be vertical rather than horizontal as with dō. Considered the hardest of all cuts was Ryo-guruma, a cut through the hips which, of course, are almost completely bone.

The sword blade itself was mounted in a strong wooden handle and it does not seem that the sword’s ordinary koshirae or mounting, was ever used when testing. This was probably because it was considered that there was a risk of damage and anyway, it was only the blade that was actually being tested. After the test was completed, the results were inscribed in detail onto the nakago or tang of the sword. This was often inlaid in gold and adds considerably to the value of the blade. Such inscriptions may often be seen on the work of the Edo swordsmiths from the Kanbun period mentioned earlier. Particularly swordsmiths such as Yamato (no) Kami Yasusada, Kasusa (no) Kami Kaneshige and Nagasone Kotetsu are noted for their sharpness, being classified as Saijo-wazamono or “supremely sharp” and often have gold inlaid cutting attestations, called a saiden-mei, on their nakago. Indeed, it is stated by Fujishiro sensei in Shinto-Jiten that much of Kotetsu’s fame and popularity in his own day, was a direct result of his close relationship with sword testers. Although most swords tested seem to have been katana or long swords, a surprising amount of wakizashi or short swords, seem to have been successfully tested. Although they were apparently tested, I have never seen the results carved onto the nakago of either yari (spears) or naginata (halberds).

Sword in mounting for testing

In my own collection, I have a sword which unusually has undergone two cutting tests and these are described on the nakago in some detail. One may make certain interesting deductions from the inscriptions. The sword is o-suriage or greatly shortened and has lost the original signature of the swordsmith, but has been attributed to Kiyomitsu of Kaga province. It is now quite a slender wakizashi or short sword and has the results of the two cutting tests inscribed on the remaining nakago. The earliest is dated 1672 and states that it cut through two dō. This may indicate that the owner needed to know that it was still an effective blade after the original shortening had taken place. It may also be deduced from the position of the hi or groove as well as the higher mekugi-ana or peg hole, that this was cut into the blade after the shortening and original cutting test but before the second test. The second test, performed in 1676, only four years after the first, states Yotsudo Dodan Barai (4 bodies cut right through to the earth mound) and then Kiri-te Nakanishi Jurobei (cut by the hand of Nakanishi Jurobei). It may be thought that the owner, once again needed to be convinced that after so many alterations had been made to his sword, it was still able to cut well and so it seems that it could. This full inscription was originally inlaid in gold, kin-zogan, and there are still small traces of it left. Unfortunately it has been painstakingly picked out for the small amount it was worth as bullion, (almost certainly after its surrender and import into the UK) but the devaluation of the sword is far greater (see *An Interesting Saidan Mei” under Articles on this website, for more on this sword)

In an old sword book entitled Token Benran, it is mentioned that the tester, Nakanishi Jurobei no Jo Yukimitsu, to give him his full name, was able to cut through three bodies and even seven! The sword which cut three bodies into the dodan was made by Hizen Ju Omi Daijo Fujiwara Tadahiro and had a straight or suguha hamon (which is often considered the sharpest hamon) and this would have been a new sword at that time. The sword which cut seven dō, was by Seki Kanefusa, had a midare hamon and was tested in the Enpo period. This latter test is often thought to be a highly exaggerated result and certainly seems strange. However, we must assume that the test was witnessed but we do not know for sure the condition or thickness of the bodies, or other precise details of the test. It is worth mentioning also that there were many variables when testing. First of course, was the blade’s sharpness, but the technique and skill of the tester, as well as the hardness and toughness of the body, might all make great differences to the result of the test.

Kinzogan Saidan Mei on a sword by Kotetsu (courtesy of Bob Benson and Bushido magazine)

There seems to have been few tests from about 1690-1780 and this was a period of where few swordsmiths of any note existed and sword production was very low, reflecting the peaceful times and decline in martial spirit of the samurai. However, by about 1780, the country was experiencing internal strife as well as having the borders of the country being tested by Western navies, trying to open trading relations. The great sword revivalist, Masahide, preached a return to the old ways of making swords and this heralded the so-called shinshinto period of sword making.

It was obvious to many samurai, often rather junior members of their clans, that there would soon be war. They supported a return of the Emperor to full ruling powers and claimed that these had been usurped by the Tokugawa family of shoguns. Additionally they felt that the shogunate were allowing foreign incursions into the country, in violation of the strict exclusion laws.

The number of swordsmiths increased and so the practice of sword testing again became popular. I have in my collection a very good sword by Koyama Munetsugu, who was the foremost swordsmith in the Bizen Ichimonji style at this time. He was a retained swordsmith of the Kuwana clan and appeared to have a keen interest in the sharpness of his blades, as many were tested by the clan’s samurai. It seems that he also had a close relationship with the Yamada Asaemon family, the official testers, and my sword was made as a gift to Yamada Asaemon Yoshimasa, the chief tester to the Tokugawa shogun. Many of Munestugu’s swords were inscribed with tests carried out at the Senju execution ground and many different cuts were used and mentioned in the nakago inscriptions, such as Ryo-guruma (hips), Taitai (chest) and chiwari (armpits). A beautifully made sword that also was capable of the most difficult cuts, is indeed a treasure.

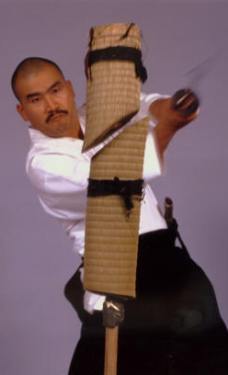

Finally, in more modern times, tests were often made in the early Showa period, the time leading up to the Pacific War. Again it was necessary for the 20th century samurai, imbued with patriotism and bushido, to know if his sword would cut. One of the most accomplished testers was a kendo master named Hakudo Nakayama. Tests were carried out on straw bales wrapped around bamboo, as this was supposed to have a similar consistency to flesh and bone. Hakudo demonstrated his skills in front of leading politicians and army officers and even in front of the Emperor on one occasion.

As swords are still made today (shinsaku-to) they are occasionally tested. I have seen a modern sword made by my Yoshihara Yoshindo, cut through an old metal helmet and, although slightly scuffed, the sword did not bend, chip or break, proving that today’s craftsmen remain true to their calling.

Source: www.to- ken.com